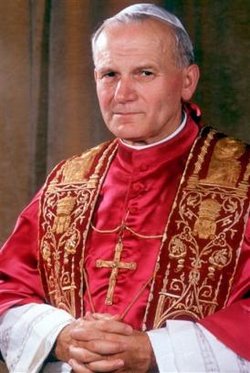

The Venerable Pope John

Paul II Latin: Sevorum Dei

Ioannes Paulus P.P. II), born Karol Józef Wojtyla (May 18 1920 – April

2 2005), was (The head of the Roman Catholic Church) Pope of the (The Christian

Church based in the Vatican and presided over by a pope and an episcopal

hierarchy) Roman Catholic Church for almost 27 years, from 16 October 1978

until his death.

He was the first non-Italian to serve in office since the (The West Germanic language of the Netherlands) Dutch- (A person of German nationality) German Pope Adrian VI died in 1523. John Paul II's reign was the third-longest in the history of the Papacy, after those of (Disciple of Jesus and leader of the apostles; regarded by Catholics as the vicar of Christ on earth and first Pope) Saint Peter (about 35 years) and Blessed Pius IX (31 years). This is in a distinctive contrast with that of his predecessor Pope John Paul I, who died suddenly after only 33 days in office, and in whose memory John Paul II named himself. The reign was marked by a continuing decline of Catholicism in industrialized nations and expansion in the (Underdeveloped and developing countries of Asia and Africa and Latin America collectively) third world.

Pope John Paul II emphasized what he called the universal call to holiness and attempted to define the Catholic Church's role in the modern world. He spoke out against ideologies and politics of (A political theory favoring collectivism in a classless society) communism, (A doctrine that advocates equal rights for women) feminism, (A policy of extending your rule over foreign countries) imperialism, ((philosophy) the philosophical doctrine that all criteria of judgment are relative to the individuals and situations involved) relativism, ((philosophy) the philosophical theory that matter is the only reality) materialism, (A political theory advocating an authoritarian hierarchical government (as opposed to democracy or liberalism)) fascism (including (A form of socialism featuring racism and expansionism) nazism), (The prejudice that members of one race are intrinsically superior to members of other races) racism and unrestrained (An economic system based on private ownership of capital) capitalism. In many ways, he fought against (A feeling of being oppressed) oppression, (A doctrine that rejects religion and religious considerations) secularism and (The state of having little or no money and few or no material possessions) poverty. Although he was on friendly terms with many Western heads of state and leading citizens, he reserved a special opprobrium for what he believed to be the corrosive spiritual effects of modern Western (A movement advocating greater protection of the interests of consumers) consumerism and the concomitant widespread secular and hedonistic orientation of Western populations.

He affirmed, explained and defined Catholic teachings on life by opposing (Termination of pregnancy) abortion, (Birth control by the use of devices (diaphragm or intrauterine device or condom) or drugs or surgery) contraception, (Putting a condemned person to death) capital punishment, embryonic (Research on stem cells and their use in medicine) stem-cell research, human cloning, (The act of killing someone painlessly (especially someone suffering from an incurable illness)) euthanasia, (The waging of armed conflict against an enemy) war and accepted ((biology) the sequence of events involved in the evolutionary development of a species or taxonomic group of organisms) evolution. He also defended traditional teachings on (The state of being a married couple voluntarily joined for life (or until divorce)) marriage and (The overt expression of attitudes that indicate to others the degree of your maleness or femaleness) gender roles by opposing (The legal dissolution of a marriage) divorce, (Two people of the same sex who live together as a family) same-sex marriage and the ordination of women. Defending Roman Catholic positions on sexual orientation he affirmed that all humans are naturally heterosexual, rejecting mainstream (A particular branch of scientific knowledge) science and opposing gay-rights. He dissented from the modern understanding of separation of church and state by calling upon Catholics to vote according to their beliefs, even if they were based on their religion and suggested that politicians who strayed be denied the (A Christian sacrament commemorating the Last Supper by consecrating bread and wine) eucharist.

John Paul became known as the "Pilgrim Pope" for having travelled greater distances than had all his predecessors combined. According to John Paul II, the trips symbolized bridge-building efforts (in keeping with his title as " Pontifex Maximus", literally "Master Bridge Builder") between nations and religions, attempting to remove divisions created through history.

It is reported that as of October 2004, he had beatified 1,340 people, more people than any previous pope. The Vatican asserts he canonized more people than the combined tally of his predecessors during the last five centuries, and from a far greater variety of cultures. Whether he had canonised more saints than all previous popes put together, as is sometimes also claimed, is difficult to prove, as the records of many early canonisations are incomplete, missing or inaccurate. However, it is known that his abolition of the office of Promotor Fidei (Promoter of the Faith, a.k.a. Devil's Advocate) streamlined the canonisation process.

Pope John Paul II died on 2 April, 2005 after a long fight against Parkinson's disease and other illnesses. Immediately after his death, many of his followers demanded that he be elevated to (Saints collectively) sainthood as soon as possible, shouting "Santo Subito". Both L'Osservatore Romano and Pope Benedict XVI, Pope John Paul II's successor, referred to John Paul II as "great." Six weeks later, on May 13, Pope Benedict formally opened the cause for ((Roman Catholic Church) an act of the Pope who declares that a deceased person lived a holy life and is worthy of public veneration; a first step toward canonization) beatification for his predecessor, which now allows Catholics to refer to Pope John Paul as "Servant of God."

John Paul was succeeded by the Dean of the ((Roman Catholic Church) the body of cardinals who advise the Pope and elect new Popes) College of Cardinals, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger of (A republic in central Europe; split into East German and West Germany after World War II and reunited in 1990) Germany, the former head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith who had led the funeral mass for John Paul.

Biography of Pope John Paul II

Early lifeKarol Józef Wojtyla

was born on 18 May, 1920 in Wadowice in southern (A

republic in central Europe; the invasion of Poland by Germany in 1939

started World War II) Poland. His mother died in 1929, and his father

supported him so that he could study. His youth was marked by intensive

contacts with the then thriving (A person belonging to the worldwide

group claiming descent from Jacob (or converted to it) and connected

by cultural or religious ties) Jewish community of Wadowice.

Karol enrolled at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. He worked as a volunteer librarian and did compulsory military training in the Academic Legion. In his youth, he was an (A person trained to compete in sports) athlete, (A theatrical performer) actor, and (Someone who writes plays) playwright, and he learned as many as eleven (A systematic means of communicating by the use of sounds or conventional symbols) languages.

During the Second World War, academics of the Jagiellonian University were arrested and the university suppressed. All able-bodied males had to have a job. He variously worked as a messenger for a restaurant and a manual labourer in a limestone quarry.

Church careerIn 1942, he entered the underground seminary run by the Archbishop of (An industrial city in southern Poland on the Vistula) Kraków, Cardinal Sapieha. Karol Wojtyla was ordained a (A clergyman in Christian churches who has the authority to perform or administer various religious rites; one of the Holy Orders) priest on 1 November 1946.

On 4 July 1958, Pope Pius XII named him titular bishop of Ombi and auxiliary to Archbishop Baziak, apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese of (An industrial city in southern Poland on the Vistula) Kraków. Karol Wojtyla found himself, at thirty-eight, the youngest (A clergyman having spiritual and administrative authority; appointed in Christian churches to oversee priests or ministers; considered in some churches to be successors of the twelve apostles of Christ) bishop in (A republic in central Europe; the invasion of Poland by Germany in 1939 started World War II) Poland.

In 1962, Bishop Karol Wojtyla took part in the Second Vatican Council, and in December 1963, ) Pope Paul VI appointed him (A bishop of highest rank) Archbishop of (An industrial city in southern Poland on the Vistula) Kraków. Pope Paul VI elevated him to ((Roman Catholic Church) one of a group of more than 100 prominent bishops in the Sacred College who advise the Pope and elect new Popes) cardinal in 1967.

A Pope from PolandIn August 1978, following Paul's death, he voted in the Papal Conclave that elected Pope John Paul I, who, at 65, was considered a young man by papal standards. Nobody could have expected that his second conclave would come so soon, for on 28 September 1978, after only 33 days as Pope, (The first Pope to assume a double name; he reigned for only 34 days (1912-1978)) John Paul I was discovered dead in the papal apartments.

Voting in the second conclave was divided between two particularly strong candidates: Giuseppe Cardinal Siri, the Archbishop of (A seaport in northwestern Italy; provincial capital of Liguria) Genoa, and Giovanni Cardinal Benelli, the Archbishop of (A town in northeast South Carolina; transportation center) Florence and a close associate of Pope John Paul I. In early ballots, Benelli came within nine votes of victory. However Wojtyla secured election as a compromise candidate, in part through the support of Franz Cardinal König and others who had previously supported Giuseppe Cardinal Siri.

He became the 264th Pope according to the Vatican (265th according to sources that count Pope Stephen II). At only 58 years of age, he was the youngest pope elected since Pope Pius IX in 1846.

Like his immediate predecessor, Pope John Paul II dispensed with the traditional Papal Coronation and instead received ecclesiastical investiture with the simplified Papal Inauguration.

Assassination attempts On 13 May 1981, John Paul II was shot and critically

wounded by

Mehmet Ali Agca, a (A Turkic language spoken by the Turks) Turkish

gunman, as he entered St. Peter's Square to address an audience. Agca

was eventually sentenced to (A sentence of imprisonment until death)

life

imprisonment. Two days after (A Christian holiday celebrating the birth

of Christ; a quarter day in England, Wales, and Ireland) Christmas

1983, John Paul visited the prison where his would-be assassin was

being held. The two spoke privately for some time. John Paul II said "What

we talked about will have to remain a secret between him and me. I

spoke to him as a brother whom I have pardoned and who has my complete

trust."

Another assassination attempt took place on 12 May, 1982, in Fatima,

Portugal when a man tried to stab John Paul II with a (A knife that

can be fixed

to the end of a rifle and used as a weapon) bayonet, but was stopped

by security guards. The assailant, an ultraconservative Spanish (A

clergyman in Christian churches who has the authority to perform or

administer various religious rites; one of the Holy Orders) priest

named Juan María Fernández y Krohn, reportedly opposed

the reforms of the Second Vatican Council and called the pope an "agent

of Moscow." He served a six-year sentence, followed by his expulsion

from Portugal.

Health John Paul II entered the papacy as a healthy, relatively young man of 58, who hiked, swam and went skiing. However, after over twenty-five years on the papal throne, two assassination attempts (one of which resulted in severe physical injury to the Pope), and a number of (Type genus of the family Cancridae) cancer scares, John Paul's physical health declined.

The 1981 assassination attempt was costlier to his overall health than was generally known by the public at the time. On the operating table his blood pressure fell dangerously low and his heartbeat was extremely weak, prompting a doctor to advise administration of the (A Catholic sacrament; a priest anoints a dying person with oil and prays for salvation) Anointing of the Sick (formerly known as " (Rites performed in connection with a death or burial) Last Rites"). There were difficulties with blood transfusions and it is believed (Any of a group of herpes viruses that enlarge epitheltial cells and can cause birth defects; can affect humans with impaired immunological systems) cytomegalovirus (CMV) was transmitted, complicating recovery. The bullet had passed completely through the body, puncturing the stomach and necessitating a (A surgical operation that creates an opening from the colon to the surface of the body to function as an anus) colostomy. Seven weeks later, discussions were held about reversing the colostomy and eight of nine doctors voted against it, arguing the Pope was still too weak from the CMV infection. Saying "I don't want to continue half dead and half alive", the Pope effectively overruled his physicians and the reversal was done successfully on August 5, 1981.

An orthopaedic surgeon confirmed in 2001 that Pope John Paul II was suffering from Parkinson's disease, as international observers had suspected for some time; this was acknowledged publicly by the Vatican in 2003. Despite difficulty speaking more than a few sentences at a time, trouble hearing and severe (Inflammation of a joint or joints) arthritis, he continued to tour the world, although rarely walking in public. Those who met him late in his life said that although physically he was in poor shape, mentally he remained fully alert.

However that claim was disputed by among others Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Mary McAleese, the (Click link for more info and facts about President of Ireland) President of Ireland, in their accounts of meetings with him in 2003. After John Paul II's death, Williams told the Sunday Times of a meeting with the Pope, during which he had paid tribute to one of John Paul's (A letter from the pope sent to all Roman Catholic bishops throughout the world) encyclicals. According to Williams, John Paul II showed no recognition. An aide whispered in the pope's ear, but was overheard reminding John Paul about the encyclical. However the Pope still showed no recognition. Papal historian John Cornwell recounted from other sources that, after Williams and his entourage left, the Pope turned to an aide and asked "tell me, who were those people". Mary McAleese told the British Catholic newspaper The Universe of a visit as President of Ireland to John Paul where he struggled to talk about the Irish College in Rome, where Irish seminarians in the city are trained and to which the Pope prior to his election had often travelled. "He wanted to be reminded of where the Irish College was, and when he heard that it was very close to St. John Lateran's basilica he wanted to be reminded where that was too."

On 1 February, 2005, the Pope was taken to the Gemelli Hospital in (Capital and largest city of Italy; on the Tiber; seat of the Roman Catholic Church; formerly the capital of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire) Rome suffering from acute inflammation of the (A cartilaginous structure at the top of the trachea; contains elastic vocal cords that are the source of the vocal tone in speech) larynx, brought on by a bout of (An acute febrile highly contagious viral disease) influenza. He was released, but in late February 2005 he began having trouble breathing, and he was rushed back. A (A surgical operation that creates an opening into the trachea with a tube inserted to provide a passage for air; performed when the pharynx is obstructed by edema or cancer or other causes) tracheotomy was performed. His doctors advised him not to try speaking.

On Palm Sunday (20 March) the Pope made a brief appearance at his window and silently waved an olive branch to pilgrims. Two days later there were renewed concerns for his health after reports stated that he had taken a turn for the worse and was not responding to medication. By the end of the month, speculation was growing, and was finally confirmed by the Vatican officials, that he was nearing death.

Death On 31 March, 2005 the Pope developed a "very high fever" (BBC News, 1 April, 2005), but was neither rushed to the hospital, nor offered life support, apparently in accordance with his wishes to die in the Vatican. Later that day, Vatican sources announced that John Paul II had been given the (A Catholic sacrament; a priest anoints a dying person with oil and prays for salvation) Anointing of the Sick. During the final days of the Pope's life, the lights were kept burning through the night where he lay in the Papal apartment on the top floor of the Apostolic Palace.

Thousands of people rushed to the Vatican, filling St Peter's Square and beyond, and held vigil for two days. In his private apartments, at 21:37 CEST (19:37 (Greenwich Mean Time updated with leap seconds) UTC) on 2 April, Pope John Paul II died 46 days short of his 85th birthday.

A crowd of over two million within Vatican City, over one billion Catholics world-wide, and many non-Catholics mourned John Paul II. The Poles, who had a deep sense of devotion towards the pontiff and referred to him as their "father," were particularly devastated by his death. The massive gathering of young people at the funeral of Pope John Paul II was referred to on the BBC as Holy Woodstock. The public viewing of his body in St. Peter's Basilica drew over four million people to Vatican City and was one of the largest (A journey to a sacred place) pilgrimages in the history of Christianity. Many world leaders expressed their condolences and ordered flags in their countries lowered to half-mast. Numerous countries with a Catholic majority, and even some with only a small Catholic population, declared mourning for John Paul II.

Funeral of Pope John Paul II

The death of Pope John Paul II set into motion (Any customary observance

or practice) rituals and traditions dating back to medieval times.

The Rite of Visitation took place from 4 April and extended through

the morning of 8 April

at St. Peter's Basilica. So many people came to see him in state that

the line had to be cut off with many people still waiting. On 8 April,

the Mass of Requiem was conducted by the Dean of the College of Cardinals,

Josef Cardinal Ratzinger (who would become the next pope).

John Paul II was interred in the grottoes under the basilica, the Tomb of the Popes. He was lowered into the (A place for the burial of a corpse (especially beneath the ground and marked by a tombstone)) tomb that had been occupied by the remains of Blessed Pope John XXIII, but which had been empty since his remains had been moved into the main body of the basilica after his ((Roman Catholic Church) an act of the Pope who declares that a deceased person lived a holy life and is worthy of public veneration; a first step toward canonization) beatification by John Paul II in 2003.

Papal conclave, 2005

Following the (A ceremony at which a dead person

is buried or cremated) funeral of Pope John Paul II, the Conclave to

elect his successor began

on April 18th. On April 19th, during the fourth round of voting, Josef

Cardinal Ratzinger of Germany was elected, and chose the name Benedict

XVI.

John Paul "The Great" Since the death of John Paul II, a number of clergy at the Vatican, including Angelo Cardinal Sodano in the written form of his homily at the Mass of Repose, have been referring to the late pontiff as "John Paul the Great"—only the fourth pope to be so acclaimed, and the first since the first millennium. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, referred to him as "the great Pope John Paul II" in his first address from the loggia of St Peter's church. One Italian newspaper, Corriere della Sera, even called him "The Greatest".

Scholars of (The body of codified laws governing the affairs of a Christian church) canon law state that there is no official process for declaring a pope "Great"; the title establishes itself through popular, and continued, usage. The three Popes who today commonly are known as "Great" are (The pope who extended the authority of the papacy to the west and persuaded Attila not to attack Rome (440-461)) Leo I, who reigned from 440– 461 and persuaded Attila the Hun to withdraw from Rome; ((Roman Catholic Church) a pope distinguished for his spiritual and temporal leadership; a saint and Doctor of the Church (540?-604)) Gregory I, 590– 604, for whom (A liturgical chant of the Roman Catholic Church) Gregorian Chant is named; and Nicholas I, 858– 867, who also withstood a siege to Rome (in this case from (A member of the Carolingian dynasty) Carolingian Christians, over a dispute regarding marriage ((law) a formal termination (of a relationship or a judicial proceeding etc)) annulment).

Beatification

Pope Benedict XVI waived the five-year waiting period

normally required before a ((Roman Catholic Church) an act of the Pope

who declares that a deceased person lived a holy life and is worthy

of public veneration; a first step toward canonization) beatification

process may begin, and on May 13, 2005, (the 24th anniversary of John

Paul II's assasination attempt,) he started the process for his predecessor.

Like other people whose beatification process is underway, the late

pope is now styled Servant of God John Paul II. However, the road to

sainthood is much longer, usually taking at least fifty years.

Life's work

TeachingsAs Pope, John Paul II's most important role was to teach people

about (The Christian Church based in the Vatican and presided over

by a pope and an episcopal hierarchy) Roman Catholic (A monotheistic

system of beliefs and practices based on the Old Testament and the

teachings of Jesus as embodied in the New Testament and emphasizing

the role of Jesus as savior) Christianity. He wrote a number of important

documents that many observers believe will have long-lasting influence

on the Church.

A great achievement of John Paul II was the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which became an international best-seller. Its purpose, according to the Pope's Apostolic Constitution Fidei Depositum was to be "a statement of the Church's faith and of catholic doctrine, attested to or illumined by Sacred Scripture, the Apostolic Tradition and the Church's Magisterium." He declared "it to be a sure norm for teaching the faith" to "serve the renewal" of the Church.

His first (A letter from the pope sent to all Roman Catholic bishops throughout the world) encyclical letters focused on the Triune God; the very first was on (A teacher and prophet born in Bethlehem and active in Nazareth; his life and sermons form the basis for Christianity (circa 4 BC - AD 29)) Jesus the Redeemer ("Redemptor Hominis"). He maintained this focus on (The supernatural being conceived as the perfect and omnipotent and omniscient originator and ruler of the universe; the object of worship in monotheistic religions) God throughout his pontificate. Right after being elected as Pope, he told the cardinals who elected him that he saw that his main work was to implement the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, an important centrepiece of which is a universal call to holiness. This is the basis for his ((Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church) the act of admitting a deceased person into the canon of saints) canonization of (A person who has died and has been declared a saint by canonization) saints from all walks of life, as well as for establishing and supporting the personal prelature of Opus Dei, whose mission is to spread this call to (Everyone except the clergy) laity and to secular priests through its association the Priestly Society of the Holy Cross.

In his master plan for the new millennium, the Apostolic Letter At the beginning of the third millennium, (" Novo Millennio Ineunte") a "program for all times", he emphasised the importance of "starting afresh from Christ": "No, we shall not be saved by a formula but by a Person." Thus, the first priority for the Church is holiness: "All Christian faithful...are called to the fullness of the Christian life." Christians, he writes, contradict this when they "settle for a life of mediocrity, marked by a minimalist ethic and a shallow religiosity." He highlighted "the radical message of the gospels," whose demands should not be watered down. The "training in holiness calls for a Christian life distinguished above all in the art of prayer." His last Encyclical is on the Holy Eucharist, which he says "contains the Church's entire spiritual wealth: Christ himself." Building on his master plan further, he emphasised the need to "rekindle amazement" on the (A Christian sacrament commemorating the Last Supper by consecrating bread and wine) Eucharist and to "contemplate the face of Christ."

In The Splendour of the Truth ("Veritatis Splendor"), a crucial papal encyclical on morality, he emphasised the dependence of man on God and his law ("Without the Creator, the creature disappears") and the "dependence of freedom on the truth." He warned that man "giving himself over to relativism and scepticism, goes off in search of an illusory freedom apart from truth itself."

John Paul II also wrote extensively about workers and the social doctrine of the Church, which he discussed in three encyclicals and which the Vatican brought to the fore through the recently published Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church. Through his encyclicals, John Paul also talked about the dignity of women and the importance of the ((biology) a taxonomic group containing one or more genera) family for the future of mankind.

Other important documents include The Gospel of Life ("Evangelium Vitae"), Faith and Reason ("Fides et Ratio"), and Orientale Lumen ("Light of the East").

John Paul II was also considered to have halted the progressive efforts of Vatican II, becoming a standard-bearer for the conservative side of the Catholic Church. He continued his staunch opposition to (An agent or device intended to prevent conception) contraceptive methods, (Termination of pregnancy) abortion and (A sexual attraction to (or sexual relations with) persons of the same sex) homosexuality. His book Memory and Identity claimed that the push for homosexual marriage might be part of a "new ideology of evil ... which attempts to pit human rights against the family and against man." However, he laid the groundwork to end the priestly celibacy requirement by welcoming many married Episcopal priests into the Church, who join those in the Eastern Rite already married.

John Paul II, as a writer of philosophical and theological thought, was characterised by his explorations in (A philosophical doctrine proposed by Edmund Husserl based on the study of human experience in which considerations of objective reality are not taken into account) phenomenology. He is also known for his development of the theology of the body.

Pastoral trips During his reign, Pope John Paul II ("The Pilgrim Pope") made over 100 foreign trips, more than all previous popes put together. In total he logged more than 1,167,000 km (725,000 miles). He consistently attracted large crowds on his travels, some amongst the largest ever assembled in human history. While some of his trips (such as to the (North American republic containing 50 states - 48 conterminous states in North America plus Alaska in northwest North America and the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific Ocean; achieved independence in 1776) United States and the (An ancient country is southwestern Asia on the east coast of the Mediterranean; a place of pilgrimage for Christianity and Islam and Judaism) Holy Land) were to places previously visited by Pope Paul VI (the first pope to travel widely), many others were to places that no pope had ever visited before. All these travels were paid by the money of the countries he visited, not by the Vatican's money.

One of John Paul II's earliest official visits was to Poland, in June 1979. While there he held mass in Victory Square in (The capital and largest city of Poland; located in central Poland) Warsaw before over two million of his countrymen.

He became the first reigning pope to travel to the United Kingdom, where he met Queen Elizabeth II, the Supreme Governor of the (The national church of England (and all other churches in other countries that share its beliefs); has its see in Canterbury and the Sovereign as its temporal head) Church of England. This trip was in danger of being cancelled due to the then current Falklands War, against which he spoke out during the visit. In a dramatic symbolic gesture, he knelt in prayer alongside the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, in the See of the (The national church of England (and all other churches in other countries that share its beliefs); has its see in Canterbury and the Sovereign as its temporal head) Church of England, Canterbury Cathedral, founded by St Augustine of Canterbury.

Throughout his trips, he stressed his devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary through visits to various shrines to the Virgin Mary, notably (The act of hitting vigorously) Knock in (An island comprising the republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland) Ireland, (Youngest daughter of the prophet Mohammed and wife of the fourth calif Ali; revered especially by Shiite Muslims (606-632)) Fátima in (A republic in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula; Portuguese explorers and colonists in the 15th and 16th centuries created a vast overseas empire (including Brazil)) Portugal, Guadalupe in (A Republic in southern North America; became independent from Spain in 1810) Mexico, and Lourdes in (A republic in western Europe; the largest country wholly in Europe) France. His public visits were centred on large Papal Masses; one million people, one quarter of the population of the island of Ireland, attended his (The property of a body that causes it to have weight in a gravitational field) Mass in (Capital and largest city and major port of the Irish Free State) Dublin's Phoenix Park in 1979.

In 1984, John Paul became the first Pope to visit (A self-governing commonwealth associated with the United States occupying the island of Puerto Rico) Puerto Rico. Stands were especially erected for him at Luis Munoz Marin International Airport in (The capital and largest city of Puerto Rico) San Juan, where he met with governor Carlos Romero Barceló, and at Plaza Las Americas.

There was a plot to assassinate the Pope during his visit to (The capital and largest city of the Philippines; located on southern Luzon) Manila in January 1995, as part of Operation Bojinka, a mass terrorist attack that was developed by (An intensely anti-western terrorist network that dispenses money and logistical support and training to a wide variety of radical Islamic terrorist group; has cells in more than 50 countries) Al-Qaeda members Ramzi Yousef and Khalid Sheik Mohammed. A (A terrorist who blows himself up in order to kill or injure other people) suicide bomber dressed as a (A clergyman in Christian churches who has the authority to perform or administer various religious rites; one of the Holy Orders) priest and planned to use the disguise to get closer to the (The head of the Roman Catholic Church) Pope's motorcade so that he could kill the Pope by detonating himself. Before 15 January, the day on which the men were to attack the Pope during his (Official language of the Philippines; based on Tagalog; draws its lexicon from other Philippine languages) Philippine visit, an apartment fire brought investigators led by Aida Fariscal to Yousef's laptop computer, which had terrorist plans on it, as well as clothes and items that suggested an assassination plot. Yousef was arrested in (A Muslim republic that occupies the heartland of ancient south Asian civilization in the Indus River valley; formerly part of India; achieved independence from the United Kingdom in 1947) Pakistan about a month later, but Khalid Sheik Mohammed was not arrested until 2003. During this trip to Philippines, on 15 January 1995, he offered mass to an estimated crowd of 4–5 million in Luneta Park, Manila, the largest papal crowd ever.

On 22 March 1998, during his second Papal visit to (A republic in West Africa on the Gulf of Guinea; gained independence from Britain in 1960; most populous African country) Nigeria, he canonized the Nigerian monk Cyprian Michael Tansi. This was a canonisation that greatly endeared the Pope to many African Catholics.

Also in 1999, John Paul II made another of his multiple trips to the United States, this time celebrating mass in (The largest city in Missouri; a busy river port on the Mississippi River near its confluence with the Missouri River; was an important staging area for wagon trains westward in the 19th century) St. Louis in the Edward Jones Dome. Over 104,000 people attended the mass, making it the biggest indoor gathering in United States history.

In 2000, he became the first modern Catholic pope to visit (A republic in northeastern Africa known as the United Arab Republic until 1971; site of an ancient civilization that flourished from 2600 to 30 BC) Egypt, where he met with the Coptic pope and the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria.

In May 2001, the Pontiff took a pilgrimage that would trace the steps of his co-namesake, (Capital of the state of Minnesota; located in southeastern Minnesota on the Mississippi river adjacent to Minneapolis; one of the Twin Cities) Saint Paul, across the Mediterranean, from Greece to Syria to Malta. John Paul II became the first Pope to visit (A republic in southeastern Europe on the southern part of the Balkan peninsula; known for grapes and olives and olive oil) Greece in 1291 years. The visit was controversial, and the Pontiff was met with protests and snubbed by Eastern Orthodox leaders, none of whom met his arrival.

In (The capital and largest city of Greece; named after Athena (its patron goddess)) Athens, the Pope met with Archbishop Christodoulos, the head of the (State church of Greece; an autonomous part of the Eastern Orthodox Church) Greek Orthodox Church in Greece. After a private 30 minute meeting, the two spoke publicly. Christodoulos read a list of "13 offences" of the Roman Catholic Church against the Orthodox Church since the Great Schism, including the pillaging of (The largest city and former capital of Turkey; rebuilt on the site of ancient Byzantium by Constantine I in the fourth century; renamed Constantinople by Constantine who made it the capital of the Byzantine Empire; now the seat of the Eastern Orthodox Chu) Constantinople by crusaders in 1204. He also bemoaned the lack of any apology from the Roman Catholic Church, saying that "until now, there has not been heard a single request for pardon" for the "maniacal crusaders of the 13th century".

The Pope responded by saying, "For the occasions past and present, when sons and daughters of the Catholic Church have sinned by action or omission against their Orthodox brothers and sisters, may the Lord grant us forgiveness," to which Christodoulos immediately applauded. John Paul also said that the sacking of Constantinople was a source of "deep regret" for Catholics.

Later, John Paul and Christodoulos met on a spot where (Capital of the state of Minnesota; located in southeastern Minnesota on the Mississippi river adjacent to Minneapolis; one of the Twin Cities) Saint Paul had once preached to Athenian Christians. They issued a "common declaration", saying, "We shall do everything in our power, so that the Christian roots of Europe and its Christian soul may be preserved. ... We condemn all recourse to violence, proselytism and fanaticism, in the name of religion." The two leaders then said the Lord's Prayer together, breaking an Orthodox taboo against praying with Catholics.

However, during the visit the Pope avoided any mention of (An island in the eastern Mediterranean) Cyprus, still a source of tension between the two faiths.

He was the first Roman Catholic Pope to visit and pray in an Islamic ((Islam) a Muslim place of worship) Mosque, in (An ancient city (widely regarded as the world's oldest) and present capital and largest city of Syria; according to the New Testament, the Apostle Paul (then known as Saul) underwent a dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus) Damascus, (An Asian republic in the Middle East at the east end of the Mediterranean; site of some of the world's most ancient centers of civilization; involved in state-sponsored terrorism) Syria. He visited Umayyad Mosque, where ((New Testament) a preacher and hermit and forerunner of Jesus (whom he baptized); was beheaded by Herod at the request of Salome) John the Baptist is believed to be interred.

In September 2001, amid post-September 11th concerns, he travelled to (A landlocked republic south of Russia and northeast of the Caspian Sea; the original Turkic-speaking inhabitants were overrun by Mongols in the 13th century; an Asian soviet from 1936 to 1991) Kazakhstan, with an audience of largely (A believer or follower of Islam) Muslims, as well as (A landlocked republic in southwestern Asia; formerly an Asian soviet; modern Armenia is but a fragment of ancient Armenia which was one of the world's oldest civilizations; throughout 2500 years the Armenian people have been invaded and oppressed by their) Armenia, to participate in the celebration of the 1700 years of (A monotheistic system of beliefs and practices based on the Old Testament and the teachings of Jesus as embodied in the New Testament and emphasizing the role of Jesus as savior) Christianity in that nation.

Relations with other religions

Pope John Paul II travelled extensively

and came into contact with many divergent faiths. With these he ceaselessly

attempted to find common ground, whether it be doctrinal or dogmatic.

He made history with his establishment of contacts with (Jewish republic

in southwestern Asia at eastern end of Mediterranean; formerly part

of Palestine) Israel, praying at the Western Wall in Jerusalem. The

(Chief lama and once ruler of Tibet) Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader

of (A Buddhist

doctrine that includes elements from India that are not Buddhist and

elements of preexisting shamanism) Tibetan Buddhism, visited Pope John

Paul II eight times, more than any other single dignitary. The Pope

and the Dalai Lama often shared similar views and understood similar

plights, both coming from peoples who have suffered under (A political

theory favoring collectivism in a classless society) communism.

In contrast, the Northern Irish Protestant leader Ian Paisley has repeatedly accused John Paul II of being the ((Christianity) the adversary of Christ (or Christianity) mentioned in the New Testament; the Antichrist will rule the world until overthrown by the Second Coming of Christ) Antichrist.

Relations of Pope John Paul II with the Jewish People

Relations between Catholicism and Judaism improved during

the pontificate of John Paul II. He spoke frequently about the Church's

relationship with (A person belonging to the worldwide group claiming

descent from Jacob (or converted to it) and connected by cultural or

religious ties) Jews. In 1979 he became the first Pope to visit the

Auschwitz concentration camp in (A republic in central Europe; the

invasion of Poland by Germany in 1939 started World War II) Poland,

where many of his countrymen had perished under Nazi rule. Shortly

afterward, he became the first modern Pope to visit a synagogue when

he visited the Synagogue of Rome on 13 April, 1986.

In March 2000, John Paul II went to the (An act of great destruction

and loss of life) Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem in (Jewish republic

in southwestern Asia at eastern end of Mediterranean; formerly part

of Palestine) Israel

and touched the holiest shrine of the Jewish people, the Western Wall

in (Capital and largest city of the modern state of Israel; a holy

city for Jews

and Christians and Muslims; was the capital of an ancient kingdom)

Jerusalem. In October 2003, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) issued

a statement congratulating John Paul II on entering the 25th year of

his papacy.

On 18 January 2005, in what would be his last public meeting, a group of 141 Jewish leaders from around the world met with Pope John Paul II in the Clementine Hall of the Apostolic Palace, to thank the (The head of the Roman Catholic Church) Pontiff for all he had done for the Jewish People and for the (Jewish republic in southwestern Asia at eastern end of Mediterranean; formerly part of Palestine) State of Israel.

Immediately after the pope's death, the ADL issued a statement that

Pope John Paul II had revolutionised Catholic-Jewish relations, saying

that "more change for the better took place in his 27 year Papacy

than in the nearly 2000 years before."

A number of points of dispute still exist between the Catholic Church

and the Jewish community, including (A war between the Allies (Australia,

Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba,

Czechoslovakia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Ethiopia, France,

Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Iran, Iraq, Luxembourg,

Mexico, Netherl) World War II-related issues and issues of doctrine.

Nonetheless, the number of issues that divide Jewish groups and the

Vatican has dropped significantly during the last forty years.

Relations with the Eastern Orthodox Church In May 1999, John Paul II visited (A Balkan republic in southeastern Europe) Romania on the invitation from His Beatitude Patriarch Teoctist of the Romanian Orthodox Church. This was the first time a Pope had visited a predominantly Eastern Orthodox country since the Great Schism in 1054, the event that separated Eastern Orthodoxy and Western (The beliefs and practices of the Catholic Church based in Rome) Roman Catholicism. On his arrival, the Patriarch and the President of Romania, Emil Constantinescu, greeted the Pope. The Patriarch stated, "The second millennium of Christian history began with a painful wounding of the unity of the Church; the end of this millennium has seen a real commitment to restoring Christian unity."

On 9 May, the Pope and the Patriarch each attended a worship service conducted by the other (an Orthodox Liturgy and a Catholic Mass, respectively). A crowd of hundreds of thousands of people turned up to attend the worship services, which were held in the open air. The Pope told the crowd, "I am here among you pushed only by the desire of authentic unity. Not long ago it was unthinkable that the bishop of Rome could visit his brothers and sisters in the faith who live in Romania. Today, after a long winter of suffering and persecution, we can finally exchange the kiss of peace and together praise the Lord." A large part of Romania's Orthodox population has shown itself warm to the idea of Christian reunification.

John Paul II visited other heavily Orthodox areas such as (A republic in southeastern Europe; formerly a European soviet; the center of the original Russian state which came into existence in the ninth century) Ukraine, despite lack of welcome at times, and he said that an end to the Schism was one of his fondest wishes.

With regard to the relations with the Serb Orthodox Church, Pope John Paul II could not escape the controversy of the involvement of Croatian Catholic clergy with the Ustasa regime of (A war between the Allies (Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Iran, Iraq, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherl) World War II. He beatified Aloysius Stepinac in 1998, the (A republic in the western Balkans in south-central Europe in the eastern Adriatic coastal area; formerly part of the Habsburg monarchy and Yugoslavia; became independent in 1991) Croatian war-time Archbishop of (The capital of Croatia) Zagreb, a move seen negatively by those who believe that he was an active collaborator with the Ustaše fascist regime. On June 22, 2003, he visited Banja Luka in (A mountainous republic of south-central Europe; formerly part of the Ottoman Empire and then a part of Yugoslavia; voted for independence in 1992 but the mostly Serbian army of Yugoslavia refused to accept the vote and began ethnic cleansing in order to r) Bosnia and Herzegovina, a city inhabited by many Catholics before the 1992-1995 war, but since then predominantly Orthodox. He held a mass at the Petricevac monastery, a place of considerable controversy and distress, both during (A war between the Allies (Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Iran, Iraq, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherl) World War II and during the Yugoslav wars.

Catholics in (A landlocked republic in eastern Europe; formerly a European soviet) Belarus (at least 10-15% of the population) had hoped for the Pope to visit their country, a trip he himself wished to make. Resistance from the Russian Orthodox Church and Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, however, meant the visit never happened.

The Pope had been also saying during his entire pontificate that one of his greatest dreams was to visit (A federation in northeastern Europe and northern Asia; formerly Soviet Russia; since 1991 an independent state) Russia, but this never occurred. He had made several attempts to solve the problems which arose over a period of centuries between the (The Christian Church based in the Vatican and presided over by a pope and an episcopal hierarchy) Roman Catholic and Russian Orthodox churches, like giving back the (An industrial city in the European part of Russia) Kazan Icon of the Mother of God in August 2004. However, the Orthodox side was not that enthusiastic, making statements like: "The question of the visit of the Pope in Russia is not connected by the journalists with the problems between the Churches, which are now unreal to solve, but with giving back one of many sacred things, which were illegally stolen from Russia." (Vsevolod Chaplin).

The Pope for youth

John Paul II had a special relationship also with

the Catholic youth and is known by some as "The Pope for Youth." He

was a hero to many of them.

He established World Youth Day in 1984 with the intention of bringing young Catholics from all parts of the world together to celebrate their faith. These week-long meetings of the youth happen every two or three years, attracting hundreds of thousands of young people, who go there to sing, party, have a good time and deepen their faith.

His most faithful youths gathered themselves in two organizations: papaboys and papagirls.

Apologies John Paul was not ignorant of Church history, and realized

that various peoples had been wronged by the Church throughout the

years. He publicly apologised for for over 100 of these mistakes, including:

On 31 October 1992, he apologised for the persecution of the Italian scientist

and philosopher (Italian astronomer and mathematician who was the first to

use a telescope to study the stars; demonstrated that different weights descend

at the same rate; perfected the refracting telescope that enabled him to make

many discoveries (1564-1642)) Galileo Galilei in the ((law) legal proceedings

consisting of the judicial examination of issues by a competent tribunal) trial

by the Roman Catholic Church in 1633.

On 9 August, 1993, he apologised for Catholic involvement with the African

slave trade.

In May, 1995, in the (A landlocked republic in central Europe; separated from

Slovakia in 1993) Czech Republic, he begged forgiveness for the Church's role

in burnings at the stake and the religious wars that followed the Protestant

Reformation.

On 10 July, 1995, he released a letter to "every woman" to apologise

for the injustices committed against women in the name of Christ, the violation

of women's rights and for the historical denigration of women.

On 16 March, 1998, he apologised for the inactivity and silence of Roman Catholics

during the Holocaust.

On 18 December, 1999, he apologised for the execution of (Czechoslovakian religious

reformer who anticipated the Reformation; he questioned the infallibility of

the Catholic Church was excommunicated (1409) for attacking the corruption

of the clergy; he was burned at the stake (1372-1415)) Jan Hus in 1415.

During a public Mass of Pardons on 12 March, 2000, he asked forgiveness for

the sins of Catholics throughout the ages for violating "the rights of

ethnic groups and peoples, and [for showing] contempt for their cultures and

religious traditions."

On 4 May, 2001, he apologised to the Patriarch of Constantinople for the sins

of the

Crusader conquest of Constantinople in 1204.

On 22 November, 2001, he apologised, via the (A computer network consisting

of a worldwide network of computer networks that use the TCP/IP network protocols

to facilitate data transmission and exchange) Internet, for missionary abuses

in the past against indigenous peoples of the (That part of the Pacific Ocean

south of the equator) South Pacific.

He also apologized for the massacre of Aztecs and other tribes by the Spanish

in the name of the Church.

Social and political stances John Paul II was a conservative on (A belief (or system of beliefs) accepted as authoritative by some group or school) doctrine and issues relating to reproduction and the (The act of ordaining; the act of conferring (or receiving) holy orders) ordination of women. His collected writings on human sexuality, called the Theology of the Body, are an extended meditation on the nature of masculinity on human life. He also extended it to condemnation of (Termination of pregnancy) abortion, (The act of killing someone painlessly (especially someone suffering from an incurable illness)) euthanasia, and virtually all uses of (Putting a condemned person to death) capital punishment, calling them all a part of the "culture of death" that is pervasive in the modern world. His stands on warfare, capital punishment, world debt forgiveness, and poverty issues were considered politically liberal, showing that 'conservative' and 'liberal' political labels are not easily assigned to religious leaders.

The Pope, who began his papacy when the (The government of the Soviet Union) Soviets controlled his homeland Poland, as well as the rest of the Eastern Europe, was a harsh critic of (A political theory favoring collectivism in a classless society) communism and offered support to those fighting for change, like the Polish (A union of interests or purposes or sympathies among members of a group) Solidarity movement. Soviet leader (Soviet statesman whose foreign policy brought an end to the Cold War and whose domestic policy introduced major reforms (born in 1931)) Mikhail Gorbachev once said the collapse of the (An impenetrable barrier to communication or information especially as imposed by rigid censorship and secrecy; used by Winston Churchill in 1946 to describe the demarcation between democratic and communist countries) Iron Curtain would have been impossible without John Paul II. This view is shared by many people of the post-Soviet states, who view him, as well as (40th President of the United States (1911-)) Ronald Reagan, as the heroes responsible for bringing an end to the communist tyranny. In later years, Pope has also criticised some of the more extreme versions of corporate capitalism.

In 2000, he publicly endorsed the Jubilee 2000 campaign on African debt relief fronted by Irish rock stars Bob Geldof and Bono. It was reported that during this period, U2's recording sessions were repeatedly interrupted by phone calls from the Pope, wanting to discuss the campaign with Bono.

In 2003, John Paul II also became a prominent critic of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. He sent his "Peace Minister", Pío Cardinal Laghi, to talk with US President (43rd President of the United States; son of George Herbert Walker Bush (born in 1946)) George W. Bush to express opposition to the war. John Paul II said that it was up to the (An organization of independent states formed in 1945 to promote international peace and security) United Nations to solve the international conflict through diplomacy and that a unilateral aggression is a crime against peace and a violation of (The body of laws governing relations between nations) international law.

In (An international organization of European countries formed after World War II to reduce trade barriers and increase cooperation among its members) European Union negotiations for a new (The act of forming something) constitution in 2003 and 2004, the Vatican's representatives failed to secure any mention of Europe's "Christian Heritage", one of the Pope's cherished goals.

The Pope was also a leading critic of (Two people of the same sex who live together as a family) same-sex marriage. In his last book, "Memory and Identity", he referred to the "pressures" on the European Parliament to permit same-sex marriage. Reuters quotes the Pope as writing, "It is legitimate and necessary to ask oneself if this is not perhaps part of a new ideology of evil, perhaps more insidious and hidden, which attempts to pit human rights against the family and against man."

The Pope also criticised (A person whose sexual identification is entirely with the opposite sex) transsexual and transgender people, as the (Click link for more info and facts about Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith) Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which he supervised, banned them from serving in church positions, as well as considering them to have "mental pathologies".

Criticism

Despite his popularity, John Paul II had many critics. One

charge sometimes levelled at the Pope was that his opposition of Communism

led him to support anti-Marxist right-wing dictators. John Paul occasionally

met with—and, some say, supported—dictators such as Augusto

Pinochet of (A republic in southern South America on the western slopes

of the Andes on the south Pacific coast) Chile. John Paul II invited

Pinochet to restore democracy, but, critics note, not in as firm terms

as the ones he used against communist countries. He allegedly endorsed

Pío Cardinal Laghi, who critics say supported the " (An

offensive conducted by secret police or the military of a regime against

revolutionary and terrorist insurgents and marked by the use of kidnapping

and torture and murder with civilians often being the victims) Dirty

War" in (A republic in southern South America; second largest

country in South America) Argentina and was on friendly terms with

the Argentinian generals of the military dictatorship, allegedly playing

regularly (A game played with rackets by two or four players who hit

a ball back and forth over a net that divides the court) tennis matches

with general Jorge Rafael Videla. When the (A state of political conflict

using means short of armed warfare) Cold War ended some conservatives

in turn argued that the Pope moved too far left on foreign policy,

and had (Someone opposed to violence as a means of settling disputes)

pacifist views that were too extreme. His opposition to the 2003 Iraq

War was thus criticized for this reason. Some on the right would also

denounce

the Pope's belief that unregulated laissez-faire capitalism was just

as harmful as socialism, arguing against any statements in which the

Pontiff was

seen to imply a moral equivalency between the two philosophies.

John Paul was also criticised for his support of the Opus Dei prelature and the ((Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church) the act of admitting a deceased person into the canon of saints) canonization of its founder, Josemaría Escrivá, whose opponents call him an admirer of (The Romance language spoken in most of Spain and the countries colonized by Spain) Spanish dictator (Spanish general whose armies took control of Spain in 1939 and who ruled as a dictator until his death (1892-1975)) Francisco Franco. Some argue that Opus Dei is essentially a (A system of religious beliefs and rituals) cult operating within the Church; John Paul saw it as part of a larger return to the Church's founding principles and his thrust to remind people of the universal call to holiness.

Besides Escrivá, several of his other canonisations and ((Roman

Catholic Church) an act of the Pope who declares that a deceased person

lived a holy life and is worthy of public veneration; a first step

toward canonization) beatifications have been criticised because the

people in question allegedly supported (An adherent of fascism or other

right-wing authoritarian views) fascist political parties. The Pope's

supporters respond that these allegations are false and some were deliberately

misconstrued by their enemies.

John Paul II made advocates of Liberation Theology unhappy by his opposition

to it.

Other criticism centred on his beliefs. In particular, John Paul's

beliefs about (The overt expression of attitudes that indicate to others

the degree of your maleness or femaleness) gender roles and (The properties

that distinguish organisms on the basis of their reproductive roles)

sexuality came under attack. Some (A supporter of feminism) feminists

criticised his positions on the role of women, and gay-rights activists

disagreed with his enunciation of the Church position that homosexual

desires are "objectively disordered", and particular opposition

to (Two people of the same sex who live together as a family) same-sex

marriage.

His beliefs about (Birth control by the use of devices (diaphragm or intrauterine device or condom) or drugs or surgery) contraception were particularly controversial to many people. John Paul followed traditional Catholic teaching and believed that one of the essential purposes of sex for a potentially fertile couple is procreation. Accordingly, he argued that using a contraceptive was an immoral act. Many people disagreed with this belief, but even some who agreed suggested that it was impractical to condemn use of condoms when sexually transmitted (A serious (often fatal) disease of the immune system transmitted through blood products especially by sexual contact or contaminated needles) AIDS is spreading. A separate but related claim is that John Paul's administration spread an unproven belief that (Contraceptive device consisting of a thin rubber or latex sheath worn over the penis during intercourse) condoms do not block the spread of (Infection by the human immunideficiency virus) HIV; between these two claims, many critics have blamed him for contributing to AIDS epidemics in (The second largest continent; located south of Europe and bordered to the west by the South Atlantic and to the east by the Indian Ocean) Africa and elsewhere. His supporters say that John Paul's stress on abstinence and fidelity has been very effective in the battle against AIDS in countries like Uganda (a recent study challenges this).

John Paul II was also sometimes criticised for the way he administered the Church; in particular, critics charged that he failed to respond quickly enough to the Roman Catholic Church sex abuse scandal. He was also criticised for recentralizing power back to the Vatican following the earlier (The spread of power away from the center to local branches or governments) decentralisation of Pope John XXIII. As such he was regarded by some as a strict (A person behaves in an tyrannical manner) authoritarian who would accept no dissent from within the church, the (The act of banishing a member of the Church from the communion of believers and the privileges of the Church; cutting a person off from a religious society) excommunication of Father Tissa Balasuriya being seen as a prime example of this by his critics.

Besides all the criticism from those demanding modernisation, Traditional

Catholics were at times equally vehement in denouncing him from the

right, demanding a return to the Tridentine Mass and repudiation of

the reforms instituted after the Second Vatican Council. Some took

their opposition

to the point of

sedevacantism while others remained within John Paul's obedience while

decrying his policies as not conservative enough.

This biography is courtesy of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia