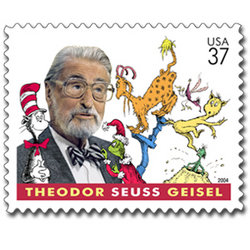

Dr. Seuss is the pen name of Theodor Seuss Geisel (March 2, 1904 – September

24, 1991). He was a famous American writer and cartoonist best known

for his children's books.

Life and Work

Geisel was born in Springfield, Massachusetts. He graduated from Dartmouth

College in 1925, where he was a member of Sigma Phi Epsilon, the

Casque & Gauntlet Society, and wrote for the Jack-O-Lantern humor

magazine under his own name and the penname "Seuss." He

entered Lincoln College, Oxford, intending to earn a doctorate in

literature. At Oxford, however, he met Helen Palmer, married her

in 1927, and returned to the United States.

He began submitting humorous articles and illustrations to Judge (a humor magazine), The Saturday Evening Post, Life, Vanity Fair, and Liberty. One notable "Technocracy Number" made fun of Technocracy, Inc. and featured satirical rhymes at the expense of Frederick Soddy. He became nationally famous from his advertisements for Flit, a common insecticide at the time. His slogan, "Quick, Henry, the Flit!" became a popular catchphrase. Geisel supported himself and his wife through the Great Depression by drawing advertising for General Electric, NBC, Standard Oil, and many other companies. He also wrote and drew a short lived comic strip called Hejji in 1935.

Even at this early stage, Geisel had started using the pen name "Dr. Seuss". His first work signed as "Dr. Seuss" appeared six months into his work for Judge. Seuss was his mother's maiden name; as an immigrant from Germany, she would have pronounced it more or less as "zoice", but today it is universally pronounced in Americanized form, with an initial s sound and rhyming with "juice". The "Dr." is an acknowledgment of his father's unfulfilled hopes that Seuss would earn a doctorate at Oxford. Geisel also used the pen name Theo. LeSieg (Geisel spelled backwards) for books he wrote but others illustrated.

In 1936, while Seuss sailed again to Europe, the rhythm of the ship's engines inspired the poem that became his first book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Seuss wrote three more children's books before World War II (see list of works below), two of which are, atypically for him, in prose.

As World War II began, Dr. Seuss turned to political cartoons, drawing over 400 in two years. Dr. Seuss's political cartoons opposed the viciousness of Hitler and Mussolini; some depict Japanese Americans as traitors. One such cartoon appeared days before the internments started.

In 1942, Dr. Seuss turned his energies to direct support of the US government's war effort. First, he worked drawing posters for the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. Then, in 1943, he joined the Army and was sent to Frank Capra's Signal Corps Unit in Hollywood, where he wrote films for the United States Armed Forces, including "Your Job in Germany," a 1945 propaganda film about peace in Europe after World War II, "Design for Death," a study of Japanese culture that won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1948, and the Private Snafu series of army training films. While in the Army, he was awarded the Legion of Merit. Dr. Seuss's non-military films from around this time were also well-received; Gerald McBoing-Boing won the Academy Award for Best Short Subject (Animated) in 1951.

Despite his numerous awards, Dr. Seuss never won the Caldecott Medal nor the Newbery. Three of his titles were chosen as Caldecott runners-up (now referred to as Caldecott Honor books): McElligot's Pool (1947), Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949), and If I Ran the Zoo (1950).

After the war, Dr. Seuss and his wife moved to La Jolla, California, a small community forming part of San Diego. Returning to children's books, he wrote what many consider to be his finest works, including such favorites as If I Ran the Zoo, (1950), Scrambled Eggs Super! (1953), On Beyond Zebra! (1955), If I Ran the Circus (1956), and How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957).

At the same time, an important development occurred that influenced much of Seuss's later work. In May 1954, Life magazine published a report on illiteracy among school children, which concluded that children were not learning to read because their books were boring. Accordingly, Seuss's publisher made up a list of 400 words he felt were important and asked Dr. Seuss to cut the list to 250 words and write a book using only those words. Nine months later, Seuss, using 220 of the words given to him, completed The Cat in the Hat. This book was a tour de force—it retained the drawing style, verse rhythms, and all the imaginative power of Seuss's earlier works, but because of its simplified vocabulary could be read by beginning readers. In 1960, Bennett Cerf bet Dr. Seuss $50 that he couldn't write an entire book using only fifty words. The result was Green Eggs and Ham. Curiously, Cerf never paid him the $50. These books achieved significant international success and remain very popular.

Dr. Seuss went on to write many other children's books, both in his new simplified-vocabulary manner (sold as "Beginner Books") and in his older, more elaborate style. The Beginner Books were not easy for Seuss, and reportedly he labored for months crafting them.

At various times Seuss also wrote books for adults that used the same style of verse and pictures: The Seven Lady Godivas, Oh, The Places You'll Go!, and his final book You're Only Old Once, a satire of hospitals and the geriatric lifestyle.

Following a very difficult illness, Helen Palmer Geisel committed suicide on October 23, 1967. Seuss married Audrey Stone Diamond on June 21, 1968. Seuss himself died, following several years of illness, in La Jolla, California on September 24, 1991.

Dr. Seuss did not like publicity. This may have been due to his German ancestry; as a schoolboy during World War I, his classmates used to nickname him "The Kaiser".

Dr. Seuss's Meters

Dr. Seuss wrote most of his books in a verse form that in the terminology

of metrics would be characterized as anapestic tetrameter, a meter

employed also by Lord Byron and other poets of the English literary

canon. (It is also the meter of the famous Christmas poem A Visit From

St. Nicholas.) Abstractly, anapestic tetrameter consists of four rhythmic

units (anapests), each composed of two weak beats followed by one strong,

schematized below:

x x X x x X x x X x x X

Often, the first weak syllable is omitted, or an additional weak syllable

is added at the end. A typical line (the first line of If I Ran the

Circus) is:

In ALL the whole TOWN the most WONderful SPOT

Seuss generally maintained this meter quite strictly, up to late in

his career, when he was no longer able to maintain strict rhythm

in all lines. The consistency of his meter was one of his hallmarks;

the many imitators and parodists of Seuss are often unable to write

in strict anapestic tetrameter, or unaware that they should, and

thus sound clumsy in comparison with the original.

Seuss also wrote verse in trochaic tetrameter, an arrangement of four units each with a strong followed by a weak beat:

X x X x X x X x

An example is the title (and first line) of One Fish, Two Fish, Red

Fish, Blue Fish. The formula for trochaic meter permits the final

weak position in the line to be omitted, which facilitates the construction

of rhymes.

Seuss generally maintained trochaic meter only for brief passages, and for longer stretches typically mixed it with iambic tetrameter:

x X x X x X x X

which is easier to write. Thus, for example, the magicians in Bartholemew

and the Oobleck make their first appearance chanting in trochees

(thus resembling the witches of Shakespeare's Macbeth):

Shuffle, duffle, muzzle, muff

then switch to iambs for the oobleck spell:

Go make the oobleck tumble down

On every street, in every town!

In Green Eggs and Ham, Sam-I-Am generally speaks in trochees, and the

exasperated character he proselytizes replies in iambs.

While most of Seuss's books are either uniformly anapestic or iambic-trochaic, a few mix triple and double rhythms. Thus, for instance, Happy Birthday to You is generally written in anapestic tetrameter, but breaks into iambo-trochaic meter for the "Dr. Derring's singing herrings" and "Who-Bubs" episodes.

Dr. Seuss's Art

Seuss's earlier artwork often employed the shaded texture of pencil

drawings or watercolors, but in children's books of the postwar period

he generally employed the starker medium of pen and ink, normally using

just black, white, and one or two colors. Later books such as The Lorax

used more colors, not necessarily to better effect.

Seuss's figures are often somewhat rounded and droopy. This is true, for instance, of the faces of the Grinch and of the Cat in the Hat. It is also true of virtually all buildings and machinery that Seuss drew: although these objects abound in straight lines in real life, Seuss carefully avoided straight lines in drawing them. For buildings, this could be accomplished in part through choice of architecture. For machines, Seuss simply distorted reality; for example, If I Ran the Circus includes a droopy hoisting crane and a droopy steam calliope.

Seuss evidently enjoyed drawing architecturally elaborate objects. His endlessly varied (but never rectilinear) palaces, ramps, platforms, and free-standing stairways are among his most evocative creations. Seuss also drew elaborate imaginary machines, of which the Audio-Telly-O-Tally-O-Count, from Dr. Seuss's Sleep Book, is one example. Seuss also liked drawing outlandish arrangements of feathers or fur, for example, the 500th hat of Bartholemew Cubbins, the tail of Gertrude McFuzz, and the pet for girls who like to brush and comb, in One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish.

Seuss's images often convey motion vividly. He was fond of a sort of "voilà" gesture, in which the hand flips outward, spreading the fingers slightly backward with the thumb up; this is done by Ish, for instance, in One Fish, Two Fish when he creates fish (who perform the gesture themselves with their fins), in the introduction of the various acts of If I Ran the Circus, and in the introduction of the Little Cats in The Cat in the Hat Comes Back. Seuss also follows the cartoon tradition of showing motion with lines, for instance in the sweeping lines that accompany Sneelock's final dive in If I Ran the Circus. Cartoonist's lines are also used to illustrate the action of the senses (sight, smell, and hearing) in The Big Brag and even of thought, as in the moment when the Grinch conceives his awful idea.

Recurring images

Seuss's early work in advertising and editorial cartooning produced

sketches that received more perfect realization later on in the children's

books. Often, the expressive use to which Seuss put an image later

on was quite different from the original. The examples below are from

the website of the Mandeville Special Collections Library of the University

of California, San Diego.

An editorial cartoon of July 16, 1941 depicts a whale resting on the

top of a mountain, as a parody of American isolationists. This was

later rendered (with no apparent political content) as the Wumbus of

On Beyond Zebra (1955). Seussian whales (cheerful and balloon-shaped,

with long eyelashes) also occur in McElligot's Pool, If I Ran the Circus,

and other books.

Another editorial cartoon from 1941 shows a long cow with many legs

and udders, representing the conquered nations of Europe being milked

by Adolf Hitler. This later became the Umbus of On Beyond Zebra.

The tower of turtles in this editorial cartoon from 1941 prefigures

a similar tower in Yertle the Turtle.

Seuss's earliest elephants were for advertising and had somewhat wrinkly

ears, much as real elephants do. With And to Think that I Saw it on

Mulberry Street (1937) and Horton Hatches the Egg (1940), the ears

became more stylized, somewhat like angel wings and thus appropriate

to the saintly Horton. During World War II, the elephant image appeared

as an emblem for India in four editorial cartoons. Horton and similar

elephants appear frequently in the postwar children's books.

While drawing advertisements for Flit, Seuss became adept at drawing

insects with huge stingers, shaped like a gentle S-curve and with a

sharp end that included a rearward-pointing barb on its lower side.

Their facial expressions depict gleeful malevolence. These insects

were later rendered in an editorial cartoon as a swarm of Allied aircraft

(1942), and later still as the Sneedle of On Beyond Zebra..

Dr. Seuss's Politics

From his work, it would appear that Dr. Seuss's political views were

what 20th century Americans would call liberal. His early political

cartoons show a passionate opposition to fascism, and he urged Americans

to oppose it, both before and after the entry of the United States

into World War II. Seuss's cartoons also called attention to the early

stages of the Holocaust and denounced discrimination in America against

black people and Jews. Seuss's harsh treatment of the Japanese and

of Japanese Americans, mentioned above, has struck many readers as

a strange moral blind spot in a generally idealistic man.

Seuss moved to La Jolla, California in 1948, following his years living and working in Hollywood. A widely told story says that when he first went to register to vote in La Jolla, some Republican friends called him over to where they were registering voters, but Ted said, "You my friends are over there, but I am going over here [to the Democratic registration]." Geisel had since been a lifelong Democrat.

Seuss's children's books also express his commitment to social justice as he perceived it, notably in five of his books:

Horton Hears a Who (1954), Horton, an open-minded elephant, finds

evidence of a world beyond our familiar one. Like Galileo Galilei or

Giordano Bruno, the authorities want to punish Horton and destroy the

evidence of his discovery. Horton maintains, however, that "A

person's a person no matter how small." Gertrude McFuzz, who lives

right next door, admires Horton for his uniqueness but fears to approach

him due to her despised one feather tail. Seuss comes out strongly

in favor of intellectual freedom.

The Sneetches and Other Stories (1961) written around the birth of

the American Civil Rights Movement, this tale of identity politics

concerns a huckster who exploits people who want to feel superior to

others based on their ethnicity.

The Lorax (1971), though told in full-tilt Seussian style, strikes

many readers as fundamentally an environmentalist tract. It is the

tale of a ruthless and greedy industrialist (the "Onceler")

who so thoroughly destroys the local environment that he ultimately

puts his own company out of business. The book is striking for being

told from the viewpoint (generally bitter, self-hating, and remorseful)

of the Onceler himself. In 1989, an effort was made by lumbering interests

in Laytonville, California to have the book banned from local school

libraries, on the grounds that it was unfair to the lumber industry.

The Butter Battle Book (1984) written in Seuss's old age, is both a

parody and denunciation of the nuclear arms race, emphasizing the reckless

and self-destructive behavior of both sides.

Seuss's personal values also are apparent in the much earlier How the

Grinch Stole Christmas (1957), which can be taken (partly) as a polemic

against materialism. The Grinch thinks he can steal Christmas from

the Whos by stealing all the Christmas gifts and decorations, and attains

a kind of enlightenment when the Whos prove him wrong.

Shortly before the end of the Watergate scandal, Geisel also converted

one of his famous children's books into a bold polemic. "Richard

M. Nixon, Will You Please Go Now!" was published in major newspapers

through the column of his friend Art Buchwald. Nine days later, Nixon

went.

Adaptations of Seuss's work

For most of his career, Dr. Seuss was reluctant to have his characters

marketed in contexts outside of his own books. However, he did allow

a few animated cartoons, an art form in which he himself had gained

experience during the Second World War.

In 1966, Seuss authorized the eminent cartoon artist Chuck Jones, his friend and former colleague from the war, to make a cartoon version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas!. This cartoon was very faithful to the original book, and is considered a classic by many to this day. In 1971, a cartoon version of The Cat in the Hat was made as well, but it was considered less successful.

Toward the end of his life, Seuss seems to have relaxed his policy,

and several other cartoons and toys were made featuring his characters,

usually the Cat in the Hat and the Grinch. When Seuss died of cancer

at the age of 87 in 1991, his widow Audrey Geisel was placed in charge

of all licensing matters. Since then, Audrey Geisel has become a controversial

figure among many of Seuss's fans, seen as being far more liberal in

permitting commercialization of her husband's characters and stories.

She approved a live-action film version of "the Grinch" starring

Jim Carrey, as well as a Seuss-themed Broadway musical called Seussical

(both released in 2000). A live-action film based on The Cat in the

Hat was released in 2003, featuring Mike Myers as the title character.

Dr. Seuss' books and characters also now appear in an amusement park:

the Seuss Landing 'island' at the Islands of Adventure theme park in

Orlando, Florida. Product tie-ins (cereal boxes, and so on) have also

been implemented.

List of books by Dr. Seuss

And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street New York: Vanguard Press,

1937

The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins New York: Vanguard Press, 1938

The King's Stilts New York: Random House, 1939

The Seven Lady Godivas New York: Random House, 1939

Horton Hatches the Egg New York: Random House, 1940

McElligot's Pool New York: Random House, 1947. Caldecott Honor Book

Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose New York: Random House, 1948

Bartholomew and the Oobleck New York: Random House, 1949. Caldecott

Honor Book

If I Ran the Zoo New York: Random House, 1950. Caldecott Honor Book

Scrambled Eggs Super! New York: Random House, 1953

Horton Hears a Who! New York: Random House, 1954

On Beyond Zebra! New York: Random House, 1955

If I Ran the Circus New York: Random House, 1956

How the Grinch Stole Christmas! New York: Random House, 1957

The Cat in the Hat New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1957

The Cat in the Hat Comes Back New York: Beginner Books, Random House,

1958

Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories New York: Random House, 1958

Happy Birthday to You! New York: Random House, 1959

One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish New York: Beginner Books, Random

House, 1960

Green Eggs and Ham New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1960

The Sneetches and Other Stories New York: Random House, 1961

Dr. Seuss's Sleep Book New York: Random House, 1962

Dr. Seuss's ABC New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1963

Hop on Pop New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1963

Fox in Socks New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1965

I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew New York: Random House, 1965

The Cat in the Hat Song Book New York: Random House, 1967

The Foot Book : Dr. Seuss's Wacky Book of Opposites New York: Bright & Early

Books, Random House, 1968

I Can Lick 30 Tigers Today! and Other Stories New York: Random House,

1969

I Can Draw It Myself New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1970

Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? New York: Bright & Early Books, Random

House, 1970

The Lorax New York: Random House, 1971. National Council for the Social

Studies Notable Children's Trade Book / Social Studies

Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now! New York: Bright & Early

Books, Random House, 1972

Did I Ever Tell You How Lucky You Are? New York: Random House 1973

The Shape of Me and Other Stuff New York: Bright & Early Books,

Random House, 1973

There's a Wocket in My Pocket! New York: Bright & Early Books,

Random House, 1974

Oh, the Thinks You Can Think! New York: Beginner Books, Random House,

1975

The Cat's Quizzer New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1976

I Can Read with My Eyes Shut! New York: Beginner Books, Random House,

1978

Oh Say Can You Say? New York: Beginner Books, Random House, 1979

Hunches in Bunches New York: Random House, 1982

The Butter Battle Book New York: Random House, 1984

You're Only Old Once! : A Book for Obsolete Children New York: Random

House, 1986.

Oh, the Places You'll Go! New York: Random House, 1990

Daisy - Head Mayzie New York: Random House, 1995

Hooray for Diffendoofer Day! New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998. By Dr.

Seuss with some help from Jack Prelutsky & Lane Smith (posthumous)

My Many Colored Days New York : Alfred A. Knopf: Distributed by Random

House, 1998. by Dr. Seuss, paintings by Steve Johnson with Lou Fancher

Gerald McBoing Boing New York: Random House, 2000 (posthumous)

This biography is courtesy of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia